Ernie Buehl and the Challenger NC5796

This article is adapted from Mark Taylor’s upcoming book, The Flying Dutchman of Philadelphia, Ernest H. Buehl. The book is expected to be out sometime in the first quarter of 2023.

Buehl started his career in Germany in 1914 as an engine builder at BMW. He was excellent at his work and quickly became their chief test mechanic. His job gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his skills internationally, and in 1920 he was recruited to come to the United States.

Here, he worked on a number of seminal projects, including the first end-to-end survey of the transcontinental airmail route. For another project, he was the mechanic responsible for making airplanes fly in the winter in the Canadian subarctic. During this period, he worked closely with Charles B. Kirkham, the chief designer of the OX-5. In fact, Kirkham traveled to Germany to bring back Buehl.

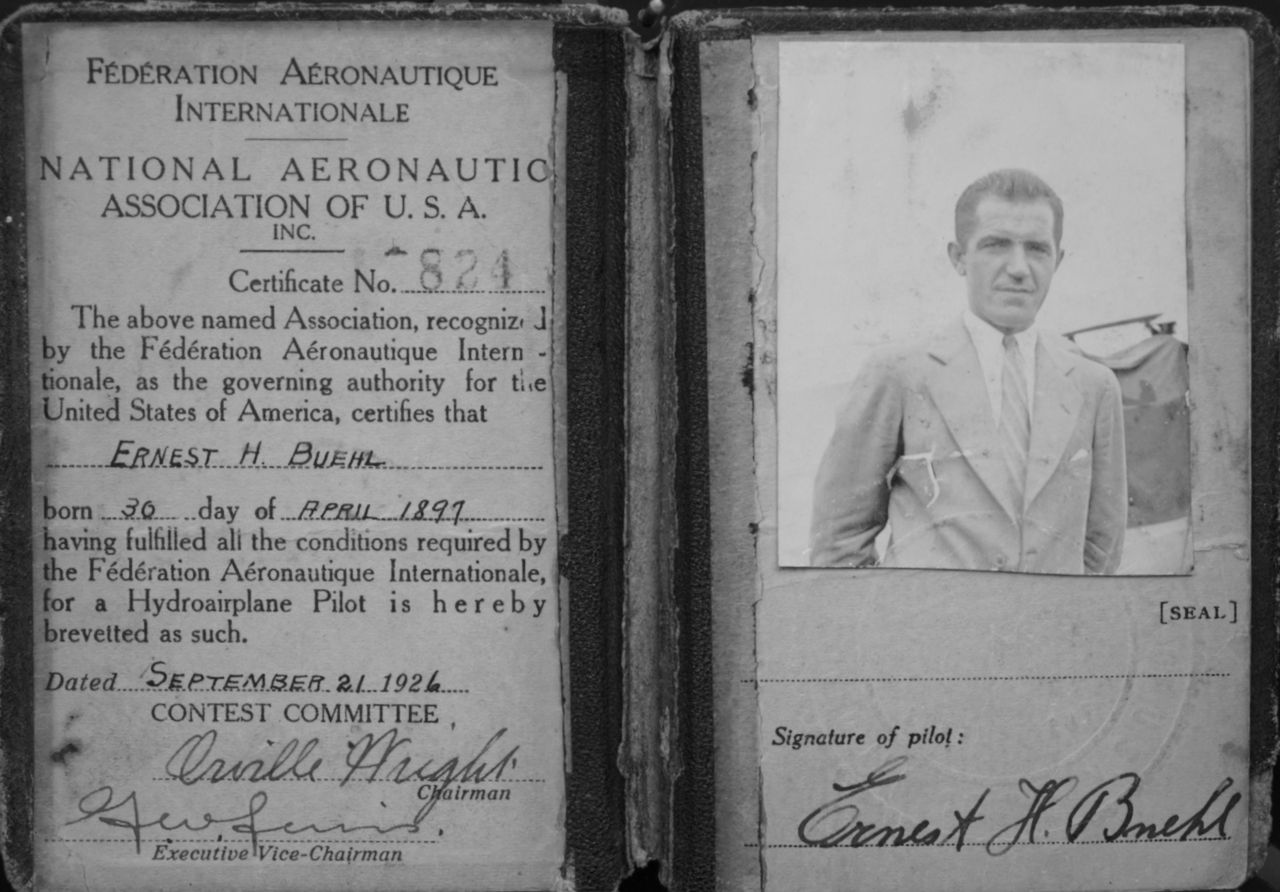

Buehl became licensed as a pilot in 1926. This was before the United States licensed pilots, so the license was issued by the FAI. He got his CAA license, the ATL, in 1928.

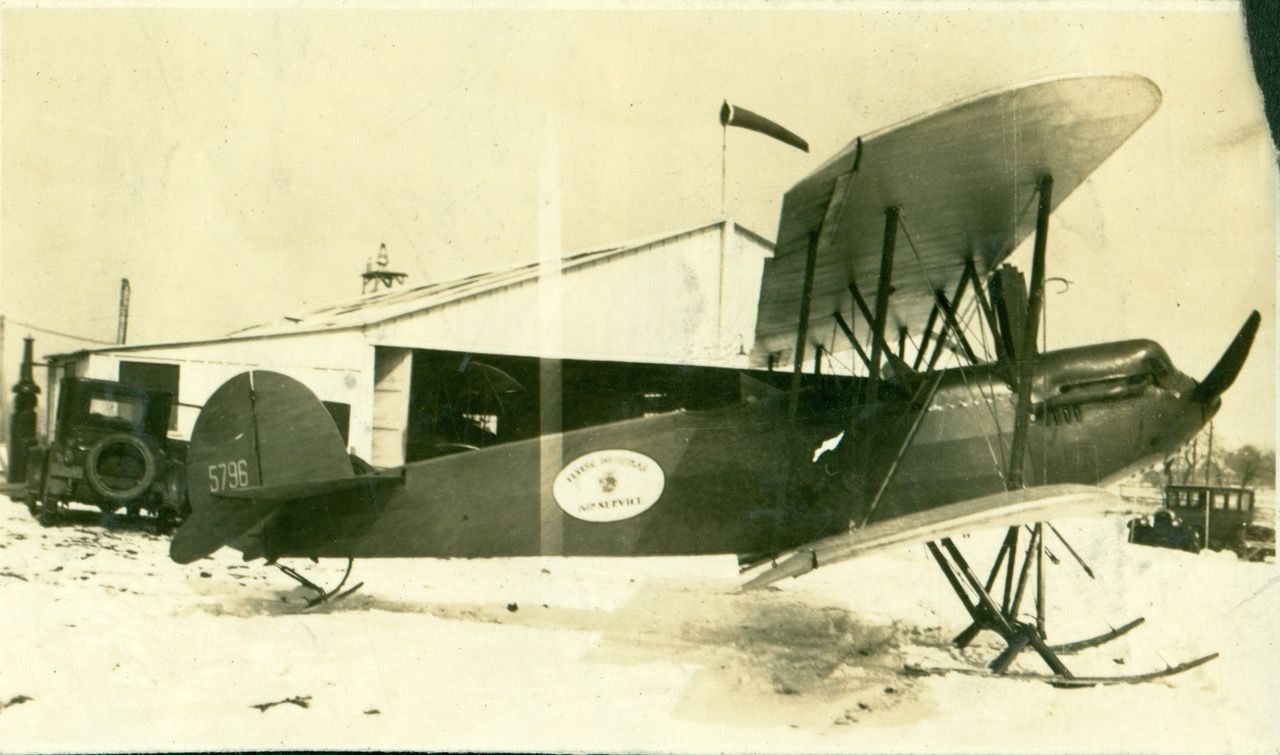

In 1928, Buehl and a partner started Flying Dutchman Air Service, which was named for Buehl (he was The Flying Dutchman, after all!). The partner, who was not a licensed pilot, owned the airplane they used. It was a Fairchild model KR-31.

By the summer of 1928, the partnership was no longer working out, so Buehl bought a 1927 model KR-31 and took over the business. The price was $2,570.

Let’s be honest. The OX-5 was a tricky engine. The valve train was fragile, and the magnetos did not hold up well. Cold weather starting was difficult, and OX-5 engines leaked coolant.

There was a story told by Brigadier General Abby Wolf about Buehl’s skill in maintaining the OX-5 engine. Wolf’s personal airplane was powered by an OX-5 engine. He was having trouble keeping it running, so he took it to the mechanics at Pitcairn. Recall that Pitcairn was not just another little airport; it was a notable aircraft manufacturer. If anyone could fix it, Pitcairn’s mechanics should be able to do it. However, they could do nothing. Perhaps it was the notoriously frustrating Berling magneto that put the problem beyond the reach of their skill? In any case, the mechanics there recommended Wolf take his airplane to Buehl. As they said, Buehl had the rare ability to keep an OX-5 running well in all seasons. When Buehl quickly solved the problem, Wolf and Buehl became lifelong friends.

Within the Buehl family, the Challenger was identified as “the OX-5,” and there was little recognition in conversations that the aircraft was actually a Fairchild.

The Challenger could always draw a crowd. In this 1957 photo, the Challenger has landed and is taxiing to its position on the tarmac at an air show at McGuire Air Force Base, near Trenton, New Jersey. Although the military aircraft on either side dwarf it, people are flocking to it for a closer look. McGuire’s base newspaper, Airtides, described Buehl’s arrival as “the outstanding action event of the day.”

Buehl kept the Challenger in flying condition for as long as he owned it. After taking the Challenger to Langhorne, Buehl stripped the linen off of the plane, recovered it entirely, and then repainted it to its original green and orange colors.

In 1982, Fairchild purchased the Challenger and put it on display at their headquarters. By 1988, Fairchild decided not to keep the Challenger. By that time, they had drained the oil and allowed the crankcase to dry out, so the engine would no longer run without extensive overhaul.

Presently, the Challenger is back in individual hands. Today, there are eight KR-31s listed in the FAA Aircraft Registration database. Buehl’s Challenger, serial number 175, was last certified as airworthy in 1972. The current owners are a husband and wife living in Woodland, California.

In late 1981, before he sold it to Fairchild, Buehl flew the Challenger one more time. He was 84 years of age.

Of course, he was forbidden to fly it. He had the diminished reflexes of old age, and because of macular degeneration, he could not see anything in front of him; he had only peripheral vision.

Buehl went to the airport office that afternoon, retrieved his flying helmet, and strapped it on. He got a little help wheeling Challenger out onto the tarmac, got in, and started its World War I era OX-5 engine. A small crowd at the airport gathered to see what he was going to do.

Buehl asked those nearby if the runway was clear. He treated the affirmative answer as though he had been given permission to take off. He waved, gunned the engine, and rolled down the runway.

It is different watching an old bi-plane take off. With so much lift from its two large wings, the Challenger did not so much zoom into the air as it would just start floating. The slow speed at which this happened can be disorienting to those who have never watched it. Before he was one-third of the way down the runway, his Challenger took off, and Buehl’s reflexes took over. He flew the airplane for a short pattern around the airport, then landed safely.

No one took pictures.